In the last post I talked about power, now let’s talk about how to figure out how much power a circuit uses. Pretty much any circuit out there can be thought of as being sort of like one big resistor. It has a resistance. The resistance of a circuit can vary depending on really anything we want it to vary on, but the same rules still apply: if we put a voltage across it, then:

[math]\latex {E =I*R}[/math]

Where E is the voltage, I is the current, and R is the resistance of the circuit. Remember: electrons are like rain drops falling from the sky. As they lose height (voltage) at a certain speed (current) they release energy over time. The amount of power they give off is equal to the height they start at (voltage) times the rate at which they lose it (current).

In other words:

[math]\latex { P=E*I}[/math]

Since

[math] \latex { \frac {E} {R} = I } [/math]

and [math] \latex { P=E*I} [/math]

then [math] \latex{P=\frac {E*E}{R}=\frac{E^2}{R}} [/math]

Isn’t math fun? If you’re as awesome as I am then you can just look at that formula and tell that the higher the resistance, the less power it will use (for a voltage source). If the resistance is too low then it will use a lot of power. In other words it will be pulling energy out at a fast rate. Where does that energy go? Well it depends on what kind of circuit this is, but if it’s just a plain old resistor then it’s being lost as heat, and if too much heat is coming out of it then it might explode.

All resistors have their own rating for how much power they can safely handle before they abuse it explode. But not to worry, we can protect it with another resistor.

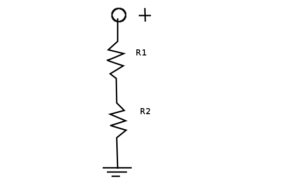

Like this:

I’m the best at drawing stuff. So R1 might be our big, bulky resistor, while R2 might be our small, wimpy one. To calculate how much power is going through each (since we’re so concerned about it) we just calculate the current going through each, and multiply it by the resistance across each one.

Since they’re in series that means that the current through both of them is the same, and that their resistances add up. So:

[math]\latex {I=\frac {V} {R1 + R2}}[/math]

And for the voltages: they’re the current multiplied by the voltage.

[math]\latex {V1=R1*\frac{V}{R1+R2}=V*\frac{R1}{R1+R2}}[/math]

This is known as the voltage divider rule. Note that for any number of resistors in series each one will be “dropping” a voltage (i.e. it will have a voltage across it), and that the voltages across all the resistors add up to V. Also note that the biggest resistor gets the most voltage, and therefore the most power.

To get the power we just multiply that by the current we calculate earlier (which is a long formula to write out).